From Kant's Categories to Geneosophy: Solving the Reality Problem

Philosophy has been wrestling with a fundamental question for centuries: How do we bridge the gap between mind and world? Each major philosophical tradition has offered solutions, but each has also revealed new problems. Today, we stand at a unique moment where quantum mechanics has deepened these puzzles while a new framework—Geneosophy—points toward a resolution.

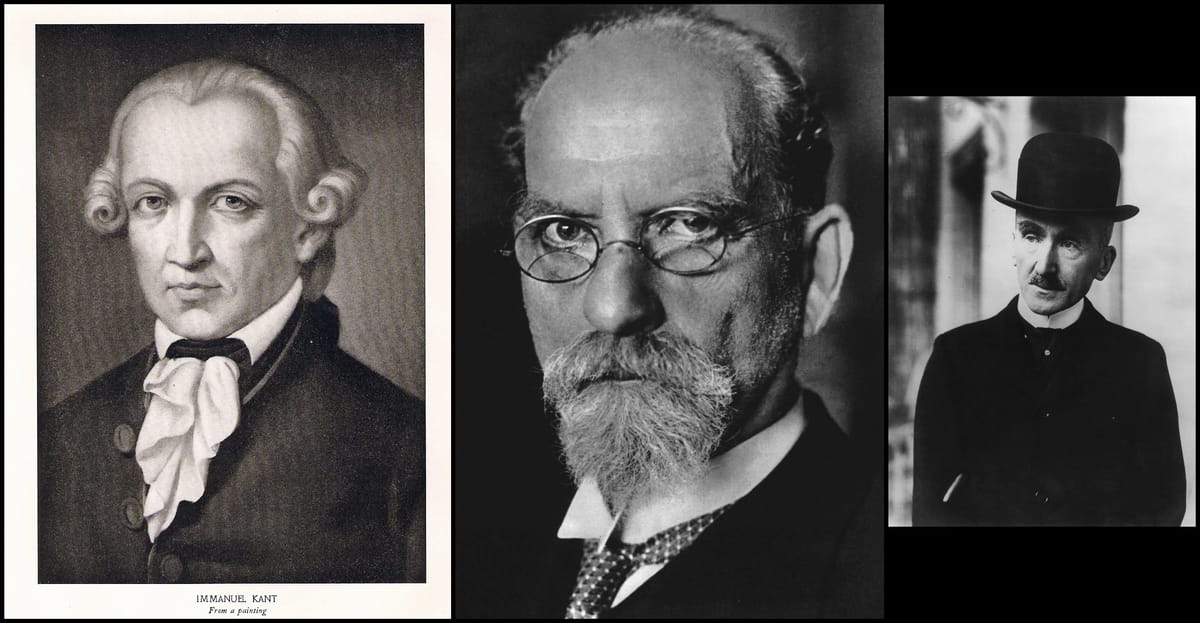

Kant's Grand Synthesis and Its Persistent Problem

Immanuel Kant faced a philosophical crisis. Empiricists like Hume argued that all knowledge comes from experience, but this led to skepticism—we could never be certain about causation or the external world. Rationalists claimed knowledge came from reason alone but struggled to connect their concepts to actual reality.

Both traditions, however, shared a crucial assumption: there exists an external world, made of either objects (for empiricists) or concepts (for rationalists), that we somehow access or represent.

Kant's revolutionary insight was to flip this relationship. Instead of our minds conforming to objects, objects conform to the structures of our minds. We don't passively receive reality—we actively construct it through a priori categories like causality, unity, and substance. When we interact with the unknowable noumena (things-in-themselves), these mental categories shape what appears to us as phenomena (the world of experience).

This was brilliant, but it created a stubborn problem: What exactly are these noumena, and how do they relate to the phenomena we experience? If things-in-themselves are completely unknowable, how can we meaningfully assert their existence? And if causality only applies to phenomena, how can noumena "cause" our experiences?

Husserl's New Direction: Consciousness as Meaning-Making

Edmund Husserl recognized the depth of Kant's noumena problem and proposed a radical solution: abandon the things-in-themselves entirely. Instead of assuming an external world that somehow produces our experiences, he focused on consciousness itself as it actually operates.

Husserl's key insight was intentionality—consciousness is always consciousness "of" something. We don't need to bridge a gap between mind and world because consciousness is already inherently directed toward objects, whether real or imaginary. The task becomes understanding how consciousness constitutes meaningful objects through its temporal flow and structural operations.

This eliminated Kant's mysterious noumena but created new puzzles: How do we move from individual consciousness to shared, objective knowledge? And how do we account for the temporal flow through which objects are constituted in consciousness?

Bergson's Temporal Revolution

Henri Bergson identified what he saw as a fundamental error in both Kant and much of the Husserlian tradition: the spatialization of time. Both approaches, he argued, treated time as a series of discrete moments rather than as the flowing, indivisible durée (duration) that we actually experience.

Bergson's insight was that life is fundamentally creative and temporal. Our intelligence, with its spatial categories and analytical habits, is adapted for practical action but misses the creative flow of lived experience. Real understanding requires intuition—a direct grasp of temporal flow that reveals life as creative evolution rather than a mechanical arrangement.

This offered a dynamic alternative to static Kantian categories, but raised its own questions: How do we move from individual intuitive insights to intersubjective knowledge? And how do we account for the apparent stability and predictability that scientific thinking captures?

Quantum Mechanics: Deepening the Mystery

Just as philosophy was grappling with these challenges, quantum mechanics introduced puzzles that seemed to vindicate some aspects of these critiques while deepening others.

Quantum mechanics suggests that properties like position and momentum don't have definite values until measured—echoing Kant's insight that objects don't have determinate properties independent of observation. The Copenhagen interpretation treats quantum mechanics as providing knowledge of phenomena while remaining agnostic about underlying reality, remarkably similar to Kant's phenomenal/noumenal distinction.

But quantum mechanics goes further: it suggests that the very act of observation partially constitutes what appears, supporting more dynamic, participatory approaches like those suggested by Husserl and Bergson. Quantum entanglement and non-locality challenge traditional notions of spatiotemporal separation that Kant saw as fundamental.

The measurement problem reveals that our classical concepts—including Kant's categories—may be inadequate for understanding the relationship between mind and physical reality at the most fundamental level.

The Geneosophy Alternative: Beyond Subject and Object

This brings us to Geneosophy, which offers a fundamentally different starting point.

The name itself reveals the core insight: gennao (to generate) plus sophia (knowledge). Instead of assuming a pre-given reality that our mind represents or constructs, Geneosophy focuses on the generative processes through which we come to experience reality and mind.

Let's name this generative process: let's call it XI—eXtended I. XI is not a traditional concept or object that exists in space and time. You should think of XI as an autonomous, creative multiplicity that interacts with a potentiality. The potentiality isn't a traditional concept either; you should think of it as the interaction environment of the XI. In a sense, potentiality shares many conceptual similarities with the interaction environment of Quantum Mechanics.

Let's keep the exposition of XI and potentiality brief for now, as this is an introductory post on Geneosophy, not a deep theoretical dive. Suffice it to say that you should think of the interaction between the XI and potentiality as the reason you experience the feeling of mind and reality, as well as all objects and concepts, including the concepts of I, time, space, and quantity. We call potentiality and XI "non-concepts" to stress that they aren't traditional concepts; otherwise, we would fall back into self-referentiality, trying to explain concepts and objects with other concepts (XI and potentiality).

We will explain how to reason about the XI and express formal hypotheses about it in Applied Geneosophy. Suffice it to say that the expression will not use mathematics or programming (otherwise, we would fall into self-reference) but a formalism specifically developed for it.

XI and potentiality are the only assumptions on which Geneosophy is based. The theory of Geneosophy is derived by logically and rationally building on these assumptions.

The Geneosophic approach dissolves several persistent problems:

- The Things-in-themselves Problem: By focusing on generation rather than representation, there's no need to postulate unknowable entities behind appearances. Reality isn't copied or constructed from pre-existing materials; rather, it is a feeling expressed by the XI.

- The Static Categories Problem: Instead of fixed a priori forms, Geneosophy emphasizes the dynamic processes through which the XI allows for the development of concepts and objects—addressing both Bergson's critique of spatial thinking and Husserl's insights about temporal constitution.

- The Individual/Universal Problem: The XI has a form that is shared by all humans and in some aspects by all organisms. Geneosophy can account for both the contextual nature of knowledge generation and its apparent universality across similar organisms.

The Quantum Connection

Geneosophy's emphasis on generative processes aligns remarkably with quantum mechanics' participatory aspects. Just as quantum measurement doesn't simply reveal pre-existing properties but participates in bringing determinate states into being, Geneosophy suggests that the XI doesn't discover reality but participate in generating it through the interaction with the potentiality.

This offers a framework for understanding how mind and physical reality are intimately connected, unlike classical approaches, without falling into the traps that caught previous philosophical systems.

The Path Forward

We stand at a moment where our most successful physical theory (quantum mechanics) suggests that mind and reality are more intimately connected than what is assumed in classical physics, while our philosophical traditions have developed sophisticated insights about temporality, intentionality, and the limits of representational thinking.

Geneosophy represents the way to synthesize these insights into a framework that can address the deep questions that have driven philosophy while remaining consistent with our best scientific understanding. It offers a path beyond the persistent puzzles that have characterized the Kantian tradition.

The test of any philosophical framework is not just its theoretical elegance, but its capacity to illuminate concrete questions such as what is intelligence and what is life. Geneosophy provides a practical framework to comprehend the concepts of life and intelligence, something that is not possible with current conceptual frameworks. Geneosophy's approach to the fundamental problems of philosophy represents a genuinely new direction.